The Ashanti Empire, also known as Asanteman, emerged in the early 18th century following its independence from the Denkyira kingdom in 1701. Under the leadership of King Osei Tutu and his spiritual advisor Okomfo Anokye, the Ashanti unified various Akan states, establishing Kumasi as the capital. The empire quickly became a dominant force in West Africa, known for its sophisticated governance, rich culture, and formidable military.

In 1820, Asantehene Osei Tutu Kwamina commissioned the construction of Fort Kumasi. Inspired by European coastal forts, the structure was built using granite and brown soil transported from Cape Coast. The fort served both as a military stronghold and a symbol of Ashanti sovereignty. Strategically located in Kumasi, it was designed to protect the empire’s capital and assert control over its vast territories.

The Ashanti Empire’s expansion and control over lucrative trade routes brought it into conflict with the British, who sought dominance in the region. This led to a series of four Anglo-Ashanti Wars:

During the second war, British forces razed Kumasi, including the original fort, as a punitive measure. The destruction marked a turning point in Ashanti resistance.

Palace of King Kwaku Dua of Kumasi, Kumasi, 1887 Kumasi

Following their victory, the British rebuilt Fort Kumasi in 1896–1897 on the ruins of the Ashanti royal palace. The new fort was intended to solidify British control over the Ashanti and northern regions of present-day Ghana. Constructed with imported materials and European design, it became a colonial military base and administrative center.

In March 1900, during the Ashanti Rebellion led by Queen Yaa Asantewaa, the fort was besieged. Twenty-nine British officials were trapped inside for weeks, highlighting the fort’s strategic importance and the enduring Ashanti resistance.

Today, Fort Kumasi houses the Ghana Armed Forces Museum, established in 1952. Located within the Uaddara Barracks in central Kumasi, the museum is one of the few military museums in Africa. It showcases:

The museum serves as a cultural and educational site, preserving the legacy of Ashanti resilience and Ghana’s military evolution. It stands as a testament to the region’s complex history of conflict, colonization, and sovereignty.

Fort Kumasi remains a powerful symbol of Ashanti pride and Ghanaian heritage, bridging the past and present through its enduring walls and historical exhibits.

Fort Kumasi remains a powerful symbol of Ashanti pride and Ghanaian heritage, bridging the past and present through its enduring walls and historical exhibits.

Opening Hours

• Tuesday to Saturday: 08:00 AM – 05:00 PM

• Sunday & Monday: Closed

Visitors are encouraged to arrive early to enjoy a full tour of the exhibits, which include colonial-era weapons, military uniforms, and historical documents.

Monday

Closed

Tuesday

08:00 - 17:00

Wednesday

08:00 - 17:00

Thursday

08:00 - 17:00

Friday

08:00 - 17:00

Saturday

08:00 - 17:00

Sunday

Closed

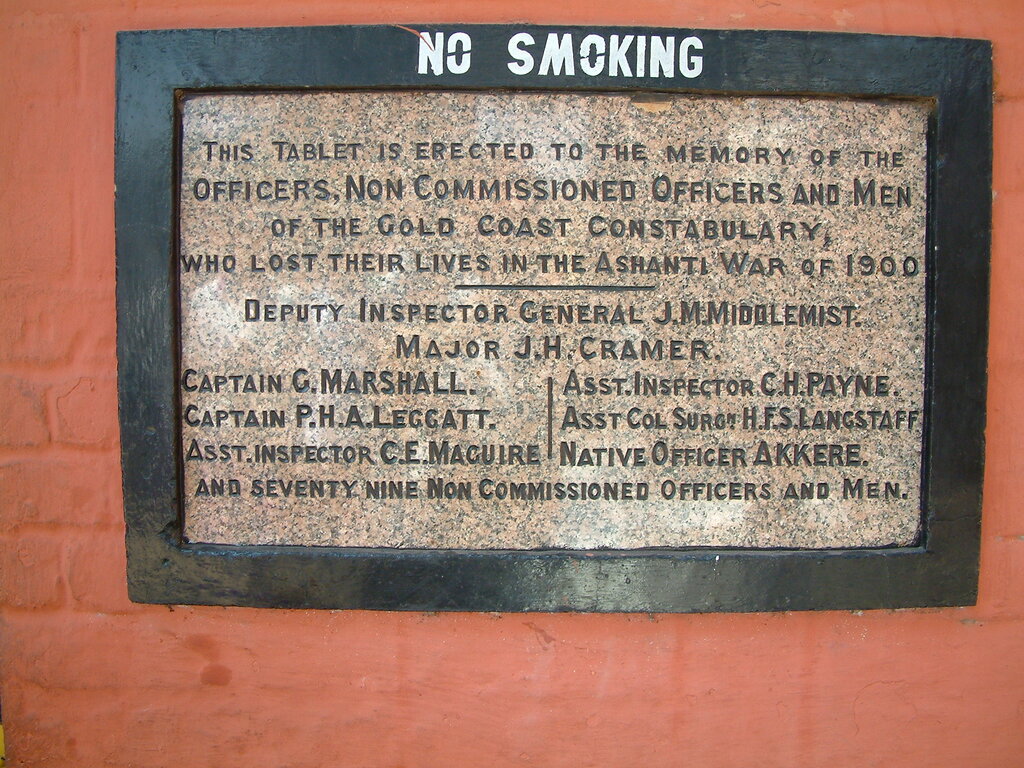

Historical Background of the Plaques

• Original Fort (1820): Built by Asantehene Osei Tutu Kwamina to resemble European coastal forts, using granite and brown soil transported from Cape Coast.

• Destruction (1874): The fort was razed by British forces during the Second Anglo-Ashanti War.

• Reconstruction (1897): The British rebuilt the fort on the ruins of the Ashanti royal palace, using similar materials and European military design.

• Siege of 1900: During the Yaa Asantewaa War, 29 British officials were trapped inside the fort for several weeks. The plaques likely reference this event and the casualties involved.

• Museum Conversion (1952–1953): The fort was repurposed as the Ghana Armed Forces Museum, and the plaques were installed to mark this transition and honor military history.

🕊️ Symbolic and Cultural Role

The granite plaques are not just historical markers—they are symbols of remembrance and reconciliation. They reflect the complex legacy of colonialism, Ashanti resistance, and Ghana’s journey toward independence. Visitors to the museum often pause at these plaques to reflect on the sacrifices made and the resilience of the Ashanti people.

Dedications to British military personnel who were stationed at the fort and those who perished during the siege of 1900. (c) Remo Kurka

The entrance gate of Fort Kumasi is one of its most visually striking features, as seen from inside. (c) Remo Kurka

Massive timber construction: The gate is made from thick, durable hardwood—likely sourced locally from Ghana’s forests. Its weight and density were intended to resist forced entry and withstand sieges.

• Iron reinforcements: Traditional wooden gates of this kind often included iron bolts, hinges, and locking mechanisms to enhance security.

• Limited access point: As with most forts, the entrance was designed to be narrow and easily defensible, allowing guards to control who entered and exited.

The heavy wooden entrance gate at Fort Kumasi is a historically significant architectural feature, designed for defense and ceremonial symbolism. While detailed records of its construction are scarce, it reflects both Ashanti craftsmanship and colonial-era military design, serving as a threshold between the fort’s exterior and its fortified interior.

🪵 Historical and Architectural Significance

The entrance gate of Fort Kumasi is one of its most visually striking features. Though not extensively documented in public archives, its design and materials suggest a blend of indigenous Ashanti woodworking traditions and European fortification principles.

🔐 Defensive Function

• Massive timber construction: The gate is made from thick, durable hardwood—likely sourced locally from Ghana’s forests. Its weight and density were intended to resist forced entry and withstand sieges.

• Iron reinforcements: Traditional wooden gates of this kind often included iron bolts, hinges, and locking mechanisms to enhance security.

• Limited access point: As with most forts, the entrance was designed to be narrow and easily defensible, allowing guards to control who entered and exited.

🏛️ Symbolic Role

• Ceremonial threshold: In Ashanti culture, gates and thresholds often carry symbolic meaning. The entrance to Fort Kumasi may have served as a ceremonial passage for military leaders and colonial officials.

• Transition marker: Architecturally, the gate marks the transition from the public exterior to the protected interior, reinforcing the fort’s role as a seat of power and control.

🧱 Integration with Fort Design

The gate is embedded within the fort’s granite walls, which were reconstructed by the British in 1897 using stone and soil transported from Cape Coast. The juxtaposition of stone and wood highlights the fusion of materials and styles that define Fort Kumasi’s architecture.

• Granite framing: The gate is set within a thick granite archway, emphasizing its defensive role.

• Courtyard access: Once inside, visitors enter the central courtyard, which historically served as a military staging area and now houses museum exhibits.

🕰️ Preservation Status

As of today, the gate remains intact and functional, maintained by the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board. It continues to serve as the main entrance to the Ghana Armed Forces Museum, welcoming visitors while preserving its historical character.

While there is limited public documentation on the gate’s original builders or exact date of installation, its enduring presence speaks to the craftsmanship and strategic foresight of both Ashanti and British engineers.

If you're planning a visit, take a moment to observe the gate’s texture, joinery, and scale—it’s a quiet but powerful witness to centuries of history.